Two paintings by Aboriginal artists, collected in Wally Caruana’s Aboriginal Art.

Paddy Jupurrurla Nelson, Paddy Japaljarri Sims, and Larry Jungarrayi Spencer, Yanjilypiri Jukurrpa (Star Dreaming), 1985 (f109).

“The Australian deserts appears empty and inhospitable to those who do not know them, but to the Aboriginal groups who inhabit these areas, the lands created by their ancestors and infused with their powers are places rich in spiritual meaning and physical sustenance.

“Geographically, the desert includes mountain ranges and spectacular rock-formations, grassy plains, strands and eucalypt and mulga trees, lakes, salt pans, sandhills, and stretches of stony country occasionally broken by seasonal watercourses and rivers and punctuated by rare permanent rockholes, springs, waterholes and soakages… Across this landscape spreads a web of ancestral paths travelled by the supernatural beings on their epic journeys of creation in the Jukurrpa or Dreaming, linking the topography firmly to the social order of the people” (p97).

“The basic elements of the pictorial art are limited in number but broad in meaning… Characteristic of the range of conventional designs and icons are those denoting place or site, and those indicating paths or movement. Concentric circles may denote a site, a camp, a waterhole or a fire. In ceremony, the concentric circle provides the means for the ancestral power which lies within the earth to surface and go back into the ground. Meandering and straight lines may indicate lightening or water courses, or they may describe the paths of ancestors and supernatural beings. Tracks of animals and humans are also part of the lexicon of desert imagery. U-shapes usually represent settled people or breasts, while arcs may be boomerangs or wind-breaks, and short straight lines or bars are often spears and digging sticks. Fields of dots can indicate sparks, fire, burnt ground, smoke, clouds, rain, and other phenomena.

“The interpretations of these designs are multiple and simultaneous, and depend on the viewer’s ritual knowledge of a site and the associated Dreaming. The meanings are elaborated and enhanced by the various combinations or juxtapositions of designs in the paintings, and also by the social and cultural contexts within which they operate — whether for ceremony or public domain, for instance. The combinations of designs allow for endless depth of meaning, and artists in decribing their work distinguish between those meanings that are indented for public revelations and those which are not, and provide the appropriate level of interpretation” (p98-99).

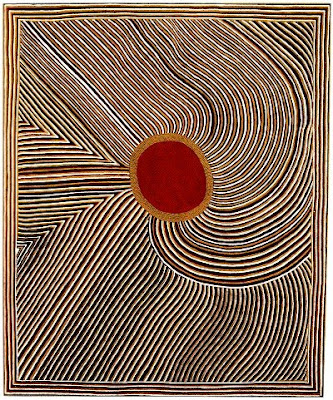

Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, Bandicoot Dreaming, 1991 (f98).

“It is by the acquisition of knowledge, not material possessions, that one attains status in Aboriginal culture. Art is an expression of knowledge, and hence a statement of authority. Through the use of ancestrally inherited designs, artists assert their identity, and their rights and responsibilities. They also define the relationships between individuals and groups, and affirm their connections to the land and the Dreaming” (p14-15).

“As a statement of authority, the aesthetic in art is often articulated in terms of ritual knowledge. Through art, individuals express their authority and knowledge of a subject, the land and the Dreaming, and artists will use their authority to introduce change and innovation” (p16).

“In ritual, paintings… are not intended to be static images requiring studied contemplation. Rather, since designs embody the power of supernatural beings, they are intended to be sensed more than viewed” (p59-60).